The Roles of the Supervisor

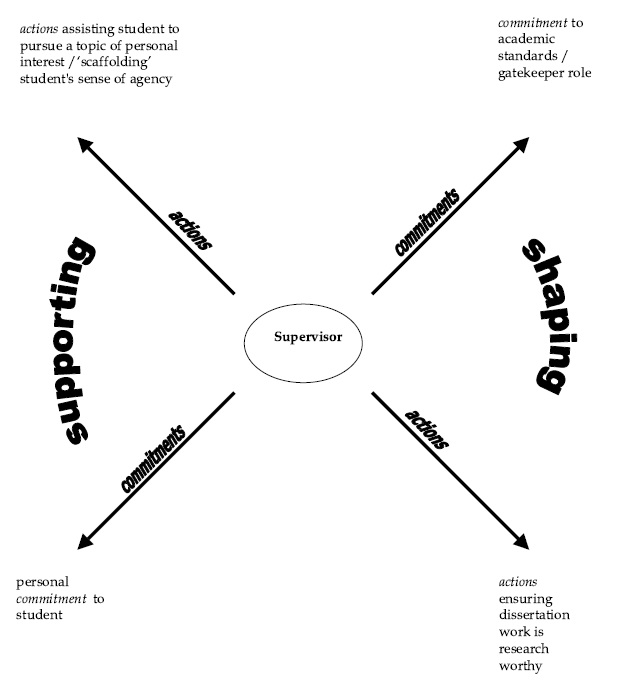

Supervision in academic settings can be understood through multiple dimensions that reflect both the responsibilities of the supervisor and the evolving needs of the student. At its core, supervision involves a dual commitment: supporting students personally and academically, while also shaping their work to meet institutional and disciplinary standards. The perspectives presented here draw on insights from two different research studies.

Perspective 1

The supervisor role can be seen as a duality of supporting and shaping students’ efforts (Anderson, Day & McLaughlin, 2006,). The above figure represents the supervisors' principal commitments on one axis and their associated actions on the other axis. It highlights that supervisors have to align students' work with academic standards. At the same time, supervisors may show personal commitment to the students. As a result, supervisors take on multiple roles—acting as gatekeepers of academic quality while also helping students pursue topics that reflect shared interests and academic relevance.

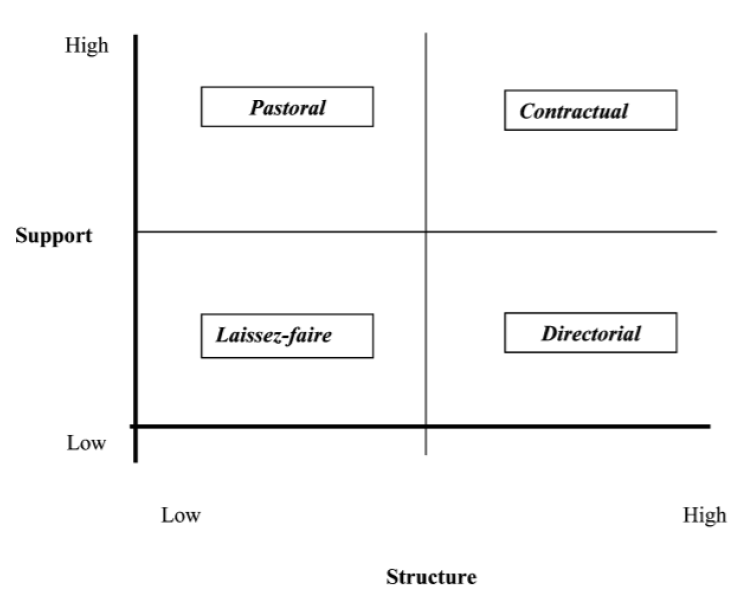

Perspective 2

The different supervision styles can be understood based on two dimensions: structure and support. From these dimensions, four paradigms of supervision styles are identified based on perceived roles in the organisation and management of the research project, supporting the candidate and resourcing the research project (Deuchar, R. (2008)). The laissez-faire style assumes that the candidates are capable of managing both their project and themselves independently. The pastoral style is described as assuming candidates can manage their project but may require personal support. The contractual style assumes that supervisors and students need to negotiate the extent of the support in both project and personal terms, whereas the directorial style assumes that the support is required in managing the project but not themselves. Each style emerges from differing assumptions about a student's need for structure and support, reflecting broader educational and institutional influences. Supervisors can reflect these styles in their own practices and adapt to the evolving needs of students.